If there’s one gripe that fans have with shojo manga, it’s the pervasiveness of weak female leads. Most readers are turned off by female protagonists who are romance-obsessed, average in looks and intelligence, and who have a tendency to be clumsy or cry a lot. In recent years, many shojo romance manga have made attempts to correct the trend of boy-crazy, passive heroines by replacing them with more assertive, independent females who have largely been embraced by the fandom. Characters such as Ouran High School Host Club‘s Haruhi and Maid-sama‘s Misaki are appreciated because of their no-nonsense attitudes, intelligence, and most of all, the fact that they are not interested in romance whatsoever. Yet, I seem to feel differently about these characters than most fans do. While characters like Haruhi and Misaki, along with Tonari no Kaibutsu-kun‘s Shizuku are considered strong female leads, they are actually more bothersome to me than their boy-crazy counterparts. One of the most common traits about this type of character is that they are often emotionally detached. Thus, not only is this the reason they’ve never had romantic feelings, but it also results in these female characters ‘going with the flow’ of their surroundings because they don’t care either way. Thus, their indifference leads them to be ‘swept off their feet’ by the guy who pursues them, rendering them passive despite their supposed ‘strength.’

Of course, boy-crazy shojo leads often end up being swept off their feet too – but since they’re interested in love and getting a boyfriend, it’s more problematic in my opinion when it happens to a ‘pseudo-feminist’ shojo lead because it’s practically against her will. But there are other problematic aspects of this type of character that disturb me even more. While so many people find the typical no-nonsense, ‘strong’ female character to be a refreshing change, I actually find these characters to be boring. I’ve written before about my problems with Haruhi’s character – that her blasé attitude toward the people and events around her made me indifferent to her character, and thus I ended up more interested in the male characters in the series just as I would have if she were a more stereotypical plain shojo lead. And while I wouldn’t call Maid-sama‘s Misaki ‘boring,’ she still somewhat annoys me because of the way the series stuffs the fact that Misaki is perfect at everything down the audience’s throats, resulting in Misaki’s strength feeling forced. Her misandry also makes her come across as ‘bitchy,’ which is bothersome because of media’s tendency to turn strong women into bitches.

And then there’s Tonari no Kaibutsu-kun‘s Shizuku. Shizuku’s probably the most extreme example of the independent shojo lead – she is only focused on studying, has no close friends, and has a brutually honest tongue. Many fans like Shizuku because she voices her honest opinions about the people around her. But something about Shizuku feels extremely robotic to me. While many fans admire the fact that Shizuku places so much importance in her schoolwork, it’s troublesome to me that when female characters are smart they are often social outcasts, as though it’s impossible for smart women to make friends on their own. Even after Shizuku tells Haru she loves him, I feel little of her emotional investment in Haru or her relationship with him. When she says that Haru has changed her world, I’m left unconvinced because Haru hadn’t been in Shizuku’s life for very long, and he had done little but be a nuisance towards her. I almost felt like she only said this line because the author ‘programmed’ her to; rather than out of genuine character development. And while fans admire Shizuku for standing up to Haru (such as when Haru tells her not to see his brother anymore and she tells him no), her motivations for doing so are left unclear, making her character feel undeveloped and unrealistic in my opinion. Thus, Shizuku’s lack of personal investment in anything leaves me uninterested in becoming invested in her.

And then there’s Tonari no Kaibutsu-kun‘s Shizuku. Shizuku’s probably the most extreme example of the independent shojo lead – she is only focused on studying, has no close friends, and has a brutually honest tongue. Many fans like Shizuku because she voices her honest opinions about the people around her. But something about Shizuku feels extremely robotic to me. While many fans admire the fact that Shizuku places so much importance in her schoolwork, it’s troublesome to me that when female characters are smart they are often social outcasts, as though it’s impossible for smart women to make friends on their own. Even after Shizuku tells Haru she loves him, I feel little of her emotional investment in Haru or her relationship with him. When she says that Haru has changed her world, I’m left unconvinced because Haru hadn’t been in Shizuku’s life for very long, and he had done little but be a nuisance towards her. I almost felt like she only said this line because the author ‘programmed’ her to; rather than out of genuine character development. And while fans admire Shizuku for standing up to Haru (such as when Haru tells her not to see his brother anymore and she tells him no), her motivations for doing so are left unclear, making her character feel undeveloped and unrealistic in my opinion. Thus, Shizuku’s lack of personal investment in anything leaves me uninterested in becoming invested in her.

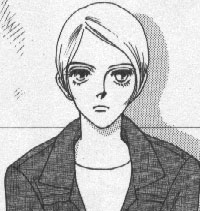

Yet there are other harsh shojo leads in the vein of Shizuku who feel genuine, and have grabbed my attention. The best example is Maria from A Devil and Her Love Song, a beautiful and intelligent transfer student who has a tendency to call people out on the kind façades they put on. While Maria says things that are truly cutting (the first thing she says to her new classmates is that she got kicked out of her previous school for beating up a teacher), she feels like a fully-dimensional character because there are tinges of sorrow to her. No matter how indifferent or cruel Maria may appear to be on the surface, it’s made clear that she wants to have friends and dislikes herself. It’s clear that she is trying to become a better person by learning to love even the people who scorn her, which has endeared her to me. More than focusing on romance, Maria’s personal struggles are what’s most important so far in A Devil and Her Love Song, which sets her apart from Shizuku. Rather than treating her bluntness as a sign of strength, Maria’s callousness is both her greatest blessing and curse, which allows her to feel more well-rounded. And while I know that there will be many fans who disagree with me for arguing that ‘no-nonsense’ characters like Haruhi and Shizuku are dull or passive, I think it’s important to question why a female character who is isn’t interested in romance or who is ‘aggressive’ should automatically be labeled strong.

Yet there are other harsh shojo leads in the vein of Shizuku who feel genuine, and have grabbed my attention. The best example is Maria from A Devil and Her Love Song, a beautiful and intelligent transfer student who has a tendency to call people out on the kind façades they put on. While Maria says things that are truly cutting (the first thing she says to her new classmates is that she got kicked out of her previous school for beating up a teacher), she feels like a fully-dimensional character because there are tinges of sorrow to her. No matter how indifferent or cruel Maria may appear to be on the surface, it’s made clear that she wants to have friends and dislikes herself. It’s clear that she is trying to become a better person by learning to love even the people who scorn her, which has endeared her to me. More than focusing on romance, Maria’s personal struggles are what’s most important so far in A Devil and Her Love Song, which sets her apart from Shizuku. Rather than treating her bluntness as a sign of strength, Maria’s callousness is both her greatest blessing and curse, which allows her to feel more well-rounded. And while I know that there will be many fans who disagree with me for arguing that ‘no-nonsense’ characters like Haruhi and Shizuku are dull or passive, I think it’s important to question why a female character who is isn’t interested in romance or who is ‘aggressive’ should automatically be labeled strong.